Aural/Oral Communication

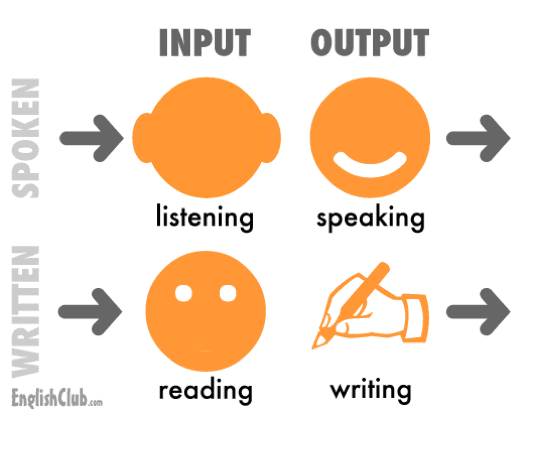

The four modalities of language are listening, speaking, reading, and writing. These are also referred to as the four language skills. Listening and reading are considered receptive skills or input, while speaking and writing are productive or output. Aural refers to hearing while oral refers to speaking. By providing an integration of each of these skills, we promote balanced language development and support multiple cognitive connections to new learning. The importance of activating prior knowledge or schema for students is based on the natural function of the brain to connect new understanding to existing understanding. New concepts are not dumped into an empty vessel called the mind. On the contrary, the brain, when presented new information, will search its existing schemata (plural for schema) to find something it can relate/connect the new information to. Physiologically, learning looks something like a tree with branches (existing neurons with dendrites that hold information) that stretch out connect to new concepts when they are presented. Visit this website to see an interactive view of how the neurological system is affected by learning. http://www.brainexplorer.org/

One of the most important concepts to keep in mind is that these 4 skills are correlated in pairs. Listening and speaking are paired in the oral area of communication, and reading and writing are in the graphic area. On the other hand, listening and reading are paired for the receptive area of communication, while speaking and writing are grouped in the productive area. Strategic development of listening, speaking, reading, and writing are essential in language acquisition.

How does this apply to language development?

Well, if we understand that new schema must chemically and physiologically “connect” to preexisting understanding (background knowledge) in order for a learner to make sense of it, then we understand why connecting to students’ prior knowledge is a necessary part of cognition. What happens when background knowledge about a topic is nonexistent? For example, if a teacher is discussing the setting of a story that takes place in the Swiss Alps, a student who has lived and experienced only tropical climates may not be able to make a connection to the setting. This child has not yet developed schema about snowy, mountainous geography and climate. The teacher in this case, would have to expose the student to images and other resources that demonstrate climates like that of the Alps in order to build enough background knowledge for the student to put the story in the context of its setting.

You may be thinking, how does this relate to listening and speaking? Well, similar to the student who had not yet developed the schema about snow, English learners are in the process of developing the schema necessary to communicate effectively through a new code made of new sounds and structures, and for many, a new alphabet as well as social and cultural norms. When we discussed phonology, we established that one’s ability to produce a sound is contingent upon his or her ability to hear that sound. If a student does not yet have the schema of a certain sound that is produced in English, he cannot yet connect to the sound in order to use it. His background knowledge must be developed. The problem is, as this student developed his first language as a child, his linguistic schemata was developed in a way that embodied a set of sounds that are specific to his first language. The process of adding new sounds to the established set, requires the physiological growth of new dendrites in the area of the brain that controls language and sends verbal commands from the brain to the mouth.